In the late 1970s, Chicago and New York’s Black & Latino gay community’s sound was defined by Disco. Danceable, emotional and DJ-led, it was a cultural movement all in of itself. It symbolised a hedonistic escape from emotional pain and dancing the night away. A mix of funk, soul, latin and psychedelic all merged into a repetitive, syncopated, four-to-the-floor sound. It was catchy, infectious and downright attention-grabbing. As Disco took root in underground gay club culture, it exploded into the mainstream of pop music, eclipsing all other sounds.

Inevitably, Disco’s mainstream dominance made it a target. Not only did many people feel disenfranchised by Disco’s seeming glamour, but a distinct lack of choice in commercial radio stations made Disco very difficult to get away from. A rebellion against Disco was inevitable, and this rebellion played out in a number of quite vociferous cultural attacks.

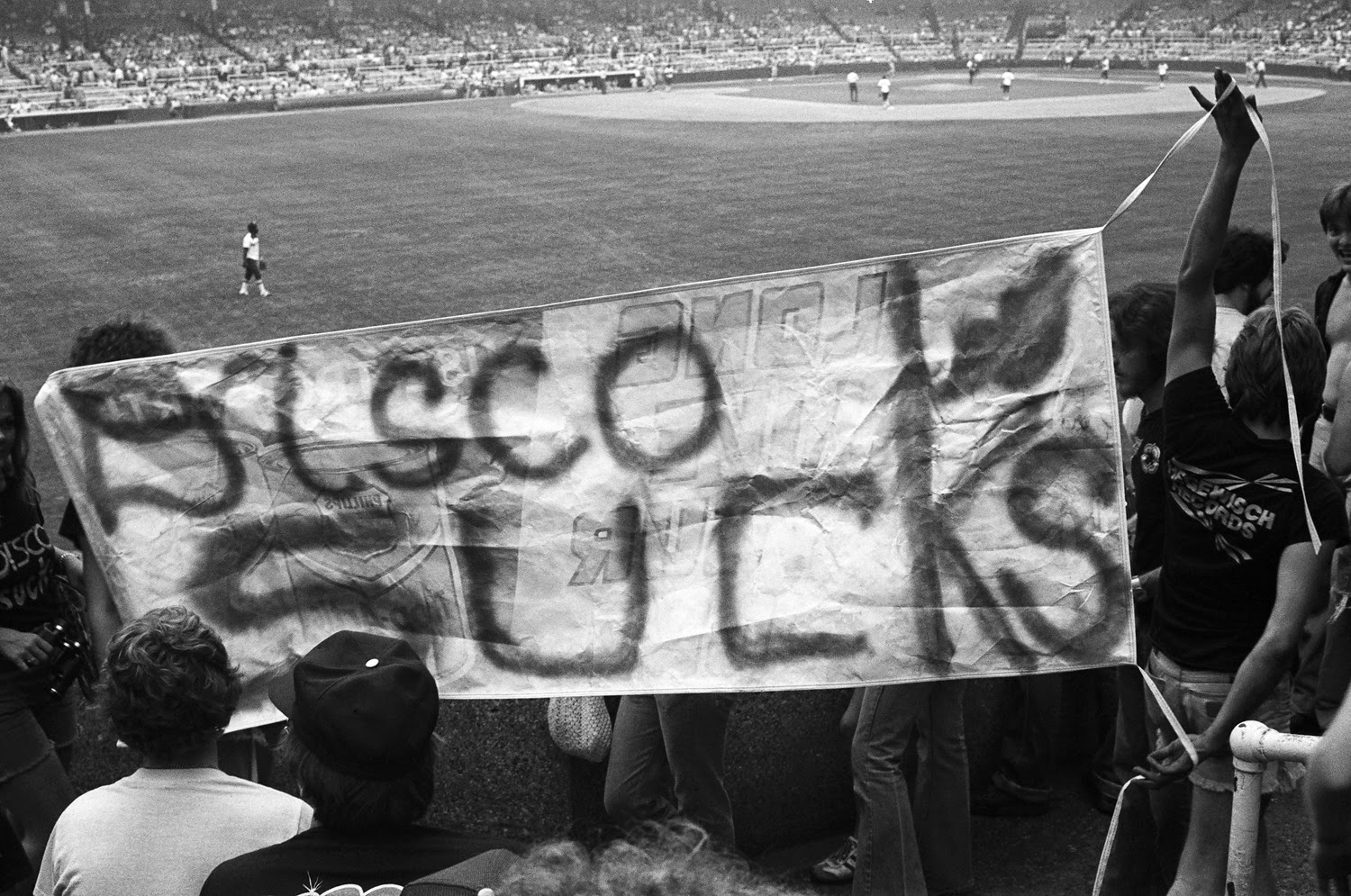

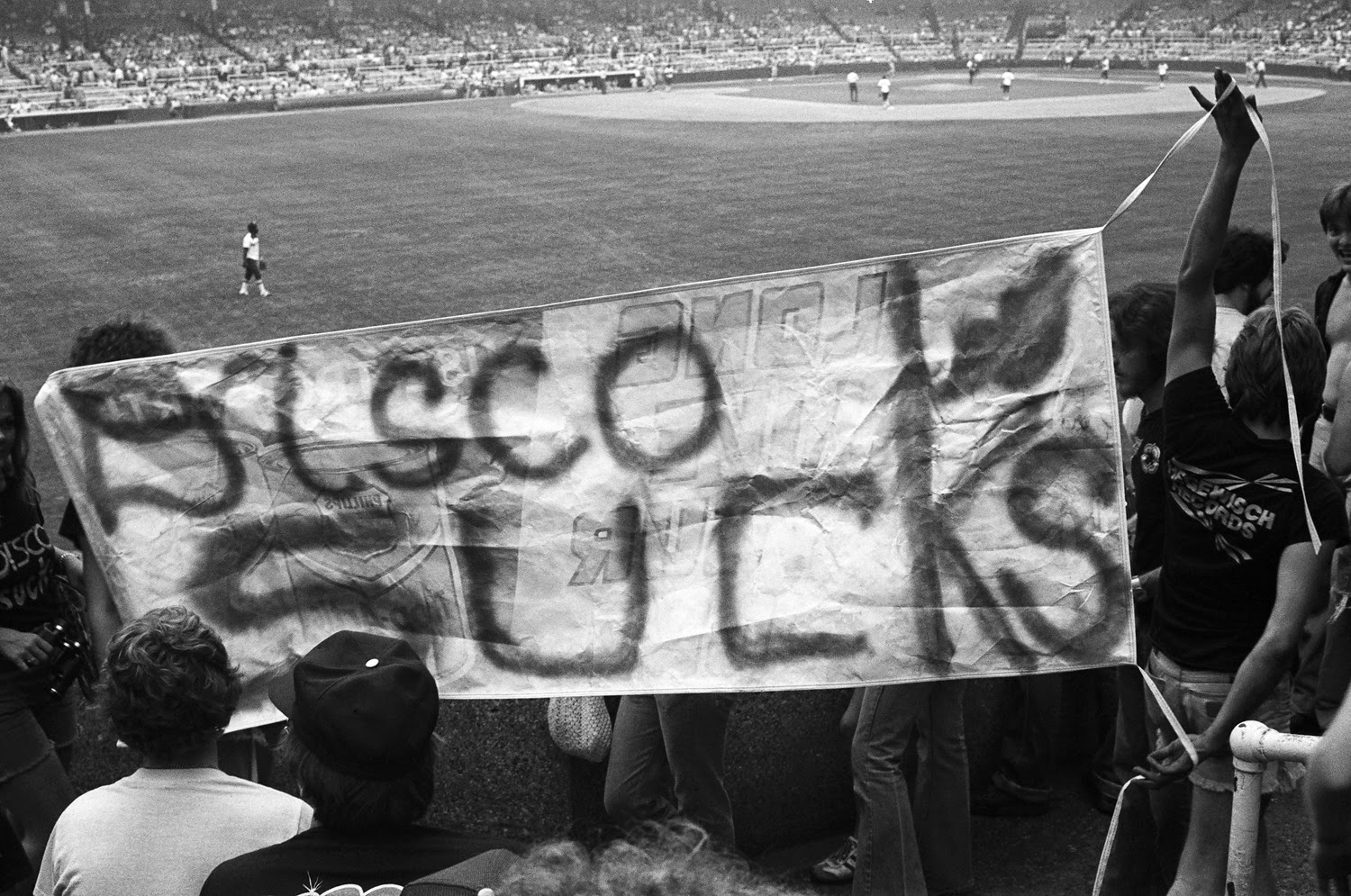

A prevalent slogan that took hold at the time was “Disco Sucks” – which more than just a direct statement of dislike – it was often used as a homophobic slur aimed at Disco’s proponents, and the people who Disco represented. This culminated in Disco Demolition Night, when 50,000 people gathered in Comiskey Park in 1979 to watch a crate of Disco records be blown up by Rock DJ Steve Dahl.

Dahl was invited to a two-night doubleheader baseball game between the Chicago White Sox and the Detroit Tigers to serve as a fun form of entertainment between the games. In the event that was scheduled, Steve organized his most magnificent destruction of Disco records ever—Disco Demolition Night. The fans attending this game were told they would be admitted to the ground for the price of 98 cents and one Disco record. These records were then placed into a big crate by ushers at the ground. Between the games, the Disco records would be carted into the middle of the field and they’d be detonated safely at the command of the famous radio star. The season had been lacklustre and the baseball teams hoped that 20,000 people would turn up, about five thousand more than normal. They were hopeful that the stunt would bring in four or five thousand, but nobody fully anticipated the amount of rage people had towards Disco.

When the gates opened to Comiskey Park, people began to pour in. At first, the teams were delighted to have the new fans. Within moments, the entire stadium was sold out. Still more people packed in by bringing Disco records as a form of payment to add to the pile. When that was stopped, others climbed the walls of the stadium or snuck in somehow. They were there to watch records get destroyed, and nobody was going to stop them. By the time that the game was underway, there were more than 50,000 people in the stadium—what’s more, the stadium wasn’t built for that. People were packed in and getting raving drunk. They were there to see not a baseball game, but a savage destruction of Disco records.

They got their fill.

Though the event started off well, the closer that they got to the detonation, the more hectic the environment became and the less control that the authorities had over the increasingly inebriated crowd. Things were getting out of control, fast. Nobody had bargained for such a rousing turnout by any means whatsoever.

Finally, the event began. A small number of people gathered in the field, mostly Steve and reporters. Explosions rocketed the field, sending shattered records flying into the air. That was all preplanned. Nobody was concerned at that point. People grew concerned when the stands lost control. People started to pour out of the stands and into the field itself. Some lobbed Disco records from the stands like frisbees. White Sox player Steve Trout recalled: “I walked out to look at centre field, and and I heard something go by me. It was an album from the upper deck and landed next to my right foot. I said ‘Holy shit, I could have been killed by The Village People”.

The authorities tried to control the masses to little success. They’d lost control. Thousands of fans stormed the field, only forced off when riot police showed up and made them evacuate and disperse. The scene marked what some historians mark as the end of the height of Disco. Though Disco held on off and on for years to come, Disco Demolition Night crippled it.

The reasons for the anti-Disco movement are myriad, and it would be unfair to suggest that racism and homophobia were the sole drivers behind it. Mainstream Disco had begun to become asinine, commercial and artificial, and music lovers without a shred of prejudice were beginning to despise it. To quote Dahl himself: “I’m worn out from defending myself as a racist homophobe for fronting Disco Demolition at Comiskey Park. This event was just a moment in time. Not racist, not anti-gay… It is important for me to have this viewed in the 1979 lens… That evening was a declaration of independence from the tyranny of sophistication.”

Regardless, it must have been difficult to be a member of the Chicago gay community at the time – to find your culture briefly gaining acceptance in mainstream society, only for 50,000 people to blow it up in a stadium.

Disco Demolition Night was symbolic of a movement and a people being pushed back underground, whereupon DJs such as Frankie Knuckles and Larry Levan began pushing the envelope, mixing glamorous, bright Disco records with the altogether darker, pulsing electronic music sound coming from Europe, including New Wave and EBM. In addition, synthesizers and drum machines were cheap – Roland’s 303, 707, 808 and 909 could often be found for very little cost in second-hand shops due to their lack of commercial appeal. This hotbed of creativity and mix of styles culminated in the creation of House music – a music that had its roots in Chicago’s gay scene.